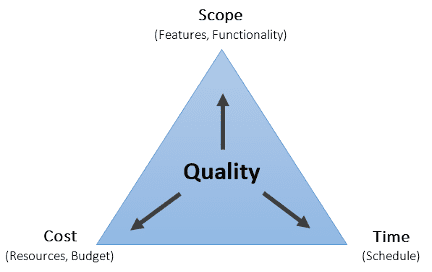

While the title may be a bit more hyperbole than you’re used to from this blog, there is actually a great deal of truth in the statement. The relationship goes back to old school project management and the realities determined by the Project Constraint Model. Namely, when it comes to scope, time, and resources, you can’t control all three at all times in a project. Or put another way, “You can have it good, fast, or cheap. Pick two.”

Source: Medium.com

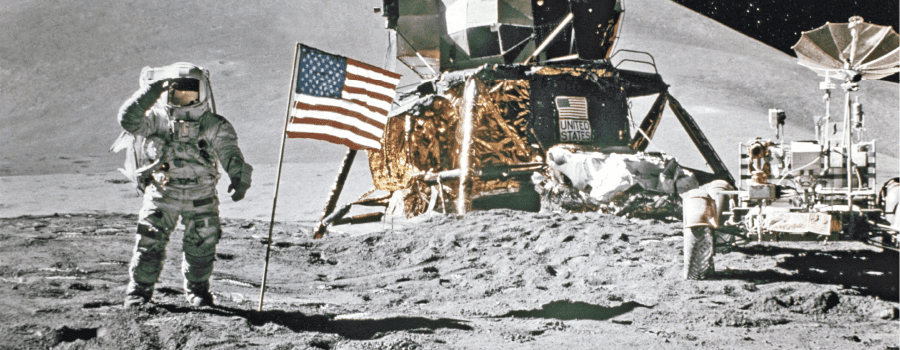

Great, but you’re probably still wondering what this has to do with landing on the Moon. Well, if we go back to the beginning, we see that President Kennedy dictated the project time/schedule—by the end of 1969. The scope is fixed, unless you can send people to space without air or spacesuits or seats… That meant that the resources were completely open-ended and could not be controlled, which is how the Apollo program ended up costing $25.4 billion or about $152 billion in today’s dollars. I’m a huge space fan and am not suggesting it was a mistake in any way, but it does show that all projects—even Moon landings—follow some basic principles. So, let’s look at a few different approaches to returning to the Moon (after an insane gap of almost 48 years and counting) and how they are trying to address the project management challenges.

Scope

Some elements of the scope of a Moon landing are non-negotiables, like the stuff related to keeping people alive and delivering them to and from the Moon safely. However, there are a lot of ways to make that happen and, while they don’t remove any of the safety criteria, they can limit the scope of new work that needs to be done. For the first Moon landings, NASA had to invent, design, build, test, and then implement everything—and I mean everything, from pens to toilets to rocket motors to docking methods. It was all on them, with partners, and they had very little historical knowledge to base their work on. There aren’t enough superlatives to describe how astounding and incredible their accomplishments were, especially given that they had virtually no computing power to help them.

Today, NASA is planning to return to the Moon with their Artemis program that will be powered by the new SLS (Space Launch System) rockets. To limit scope, time, and (theoretically) resources/cost, they chose to modify rocket motors that were used for the Space Shuttle main engines. Starting with a small number that were moth-balled after the shuttle’s retirement, they made modifications to improve efficiency, power, and reliability. Reuse is a great strategy to decrease and/or control the scope of a project. In software, we build reusable libraries, frameworks, and APIs that are then used in future projects, reducing the amount of software or functionality that must be “invented” for each new project.

Another approach to this is to simplify the approach or design. SpaceX has taken this approach with their Falcon Super Heavy and Starship launch vehicles. Together, they are built to take people to the Moon and Mars. Where NASA’s approach uses multiple spacecraft to accomplish the task—a multi-stage launch vehicle, lunar gateway, lander, and return capsule—SpaceX has a two-part vehicle that will do the whole thing (some refueling and assembly required). Again, this is a common approach in software because we can reduce the complexity required to build, test, and integrate each piece of the whole if the design is simpler and requires fewer interconnecting parts.

Time

The approaches above can also provide benefits in the area of time, but we’ll look at a couple of others that may more directly impact the time it takes to reach completion. President Kennedy took this off the table by dictating the timeline. While this is certainly one approach, it adversely impacts our efforts around scope and cost, and ultimately can lead to lower overall quality. One approach that NASA has used in the Artemis program is to have separate teams/partners working in parallel on different aspects of the program. So, while one company is working through the Orion capsule to get the astronauts to and from space, other companies are working on the different stages of the launch vehicle, the lunar gateway, and the lander that the astronauts will use to land on the Moon and return to orbit. Software development leans on this all the time, assuming the resources are available to support it. Of course, there’s some work around integrating the components in the end, but if the teams communicate well and work together to make sure the integration points are well-defined, this approach can speed things along in many cases.

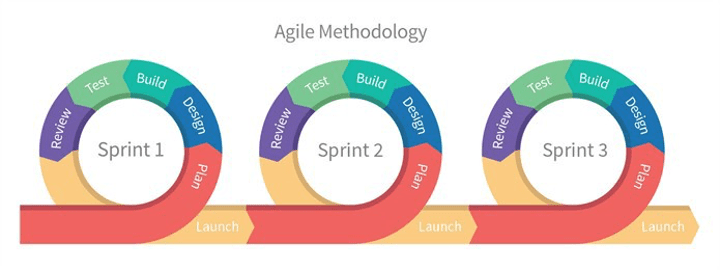

Another approach that SpaceX exemplifies in almost everything we can see them doing is to utilize iterative development. Instead of spending years coming up with the perfect complete design, building it, testing it, and then finding the issues that send you back to the start, they build the minimum necessary to test out key functionality. Then they test it, make changes to correct anything they don’t like, and do it all over again. This happens extremely fast and allows them to keep iterating their designs so that the end product is generally far better than they originally planned, while getting there faster and with less waste. The analogue in software is the use of an agile methodology. This is something that I strongly believe has the power to transform a team and an entire organization, if embraced fully. Through small, quick iterations, you get to the best solution faster.

Source: Medium.com

Resources/Cost

This one is a bit harder to discuss in terms of a Moon landing. While NASA has more recently started to include commercial partners on fixed-price contracts to limit their spend on components like the lunar lander, they have still spent an enormous amount of money and plan to spend even more. It’s hard to know how much SpaceX is spending, but from everything they’ve said, it’s an order of magnitude less – and that still might be too high of an estimate. I expect that the approaches to scope and time described above have played a large part in containing cost—and that’s without accounting for the fact that they are attacking the problem in a new and unique way, which seems to provide a lot of benefits for them.

Conclusion

First of all, I have glossed over and oversimplified what NASA and SpaceX have done and are doing to make my points easier and keep this to fewer than a million words. As Elon Musk, and probably every one of us who have studied rockets and space flight, has said, “Rockets are hard!” And that might be the understatement of all time. The lessons that can be learned from watching these extraordinary efforts play out in public are too numerous to cover here. Hopefully, this at least gives you enough information to want to dive a little deeper on either agile methodologies or rocket launches/missions. This is for the record.

For The Public Record is a monthly blog featuring thought leadership from the most seasoned experts at ClearStar, across all functions of the background screening process. Click here to subscribe.